It's a great pleasure to share this article which appears in the September-October 2020 edition of Pro AVL Asia. In the article, Richard Lawn explores Marshall Day's history in China and some of the many spectacular performing arts centres we've been involved with over the past two decades.

Original article published in September-October 2020 Pro AVL Asia: see the full issue here.

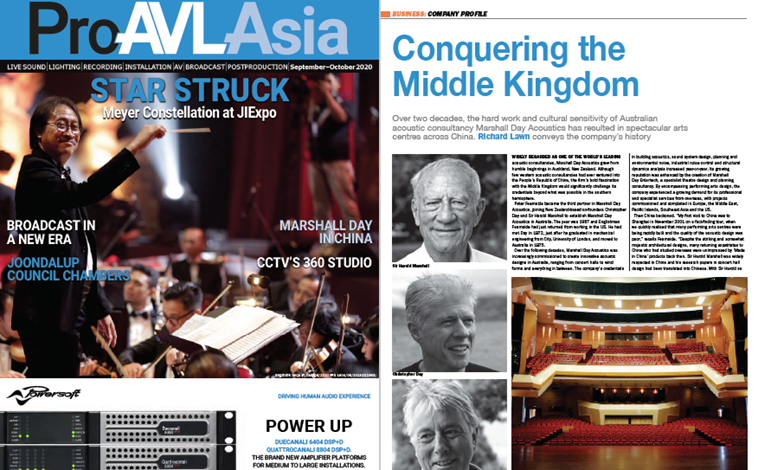

WIDELY REGARDED AS ONE OF THE WORLD’S LEADING acoustic consultancies, Marshall Day Acoustics grew from humble beginnings in Auckland, New Zealand. Although few western acoustic consultancies had ever ventured into the People’s Republic of China, the firm’s bold fascination with the Middle Kingdom would significantly challenge its credentials beyond what was possible in the southern hemisphere.

Peter Fearnside became the third partner in Marshall Day Acoustics, joining New Zealand-based co-founders Christopher Day and Sir Harold Marshall to establish Marshall Day Acoustics in Australia. The year was 1987 and Englishman Fearnside had just returned from working in the US. He had met Day in 1972, just after he graduated in mechanical engineering from City, University of London, and moved to Australia in 1975.

Over the following decades, Marshall Day Acoustics was increasingly commissioned to create innovative acoustic designs in Australia, ranging from concert halls to wind farms and everything in between. The company’s credentials in building acoustics, sound system design, planning and environmental noise, industrial noise control and structural dynamics analysis increased year-on-year.

Its growing reputation was enhanced by the creation of Marshall Day Entertech, a specialist theatre design and planning consultancy. By encompassing performing arts design, the company experienced a growing demand for its professional and specialist services from overseas, with projects commissioned and completed in Europe, the Middle East, Pacific Islands, Southeast Asia and the US.

Then China beckoned. “My first visit to China was to Shanghai in November 2001 on a fact-finding tour, when we quickly realised that many performing arts centres were being rapidly built and the quality of the acoustic design was poor,” recalls Fearnside. “Despite the striking and somewhat majestic architectural designs, many returning expatriates to China who had studied overseas were unimpressed by ‘Made in China’ products back then. Sir Harold Marshall was widely respected in China and his research papers in concert hall design had been translated into Chinese. With Sir Harold so highly regarded, we decided to select China as a potential new business territory.”

It would be just over a year before Marshall Day made its first bid on a project in Beijing. “The temperature in Melbourne was in the high 30s but, when I went to meet the head of Beijing TV, it was below zero with a significant wind chill factor and a deep covering of snow. I only became aware of just how cold it was the day before I left, and had to borrow a very large woollen overcoat from a friend as it was impossible to buy any winter clothing in the middle of January in Melbourne.”

Having adjusted to seasonal differences in weather, Fearnside then set about negotiating the many obstacles in doing business. “You can’t succeed in China without someone that you totally trust, who can speak Mandarin and possibly Cantonese, write impeccable reports in Chinese and English, and work exclusively for you. Translating technical English into Chinese is a complex task that requires a deep understanding of the language and the subject matter.”

Enter Xiaojun Du, a graduate of Shanghai University with a Masters in Structural Dynamics from Melbourne’s Monash University. Du’s help in assisting Marshall Day in its Chinese quest ensured that the formidable obstacles it would encounter either vanished or diminished in size.

“Du’s ability to translate Sir Harold’s work into Chinese helped open doors for us,” continues Fearnside. “Once Du had mastered the technical translations and successfully added Chinese subtitles to our presentations, we had created a powerful calling card.” Having avoided the trap of setting up a joint venture with another Chinese company, Fearnside admits that he learnt other Sino-Australian trade aspects the hard way. “We soon realised that we had to supply bilingual Chinese–English reports and, in doing so, we could not trust a Chinese interpreter or translator with material of a technical nature. When you write your own contract in Chinese, you have made a declaration that you fully understand the contract. It is legally binding and the English version you understand should be considered purely as a guide.”

Together with their colleagues Marshall, Peter Exton and Tim Marks, they made a formidable team. “Du taught us about negotiating at three tier levels,” explains Fearnside. “In China, you need to win over the well-connected party officials who set up the project companies, for it is they that have the ultimate control of whether you are appointed or not. At the second level, the project owners are ultimately responsible for employing you and delivering the project, and at the third level are the technicians and project managers who you will need to work with. It is essential that all these individuals or groups are won over if you are to succeed.”

Du’s inside knowledge of doing business in Chinese, together with his proficient command of the language, served as a powerful catalyst. In addition, Marshall Day received a further boost from a new source within the Australian Trade Commission in Beijing: New Zealander Carolyn Hughes. “We owe much of our early success to Carolyn,” explains Fearnside. “Unlike the other Austrade trade commissioners, who were comfortable assisting Australian companies trying to sell goods rather than services, Carolyn understood acoustics and theatre design, and where we could fit into the increasing number of arts centres being built in China. Not only did she teach us about the importance of developing relationships first before trying to do business, she also guided us on how to approach meetings. That meant learning to relax during the first hour of pleasantries regarding family and travel, and avoiding my natural instincts for a full-frontal attack on the subject at hand. Most importantly, she taught me that, in China, you need to concede many points if you want to succeed, to know the battles you need to win and those that, in the big picture, are unimportant.

“In our early days of negotiating on the Beijing TV project, we would tell Carolyn the subjects that we would be meeting. She in turn would tell us how important they were. On a few occasions, she considered a meeting so important she would arrive in the Australian Embassy limousine complete with flag on the bumper and accompany us to a meeting with top party officials. She also taught me to count the dishes at lunch or dinner, saying that if you get to 21, you are assured of a contract. At Beijing TV, I had my first 21-course lunch and we had our first performing arts project in China. There have now been over 15 concert halls, 20 opera theatres and 25 theatres throughout the length and breadth of the Middle Kingdom.”

In the early days, the company learned to conduct one project at a time, finding that this strategy helped it to progress courtesy of word-of-mouth referrals. “Doing business in China is not for the faint-hearted,” continues Fearnside. “If you don’t fall in love with the country, the people, the food, the gigantic cities and the speed at which buildings are designed and built, it’s better to look somewhere else. I rapidly grew to love China and, for the next 17 years, I flew there over 60 times. In that time, I have been fortunate to visit almost all of the largest cities with a population in excess of 10 million and work on the design of performing arts centres in Beijing, Nanjing, Xian and Chengdu.”

Biggest is not always best, however. “I have also visited delightful smaller cities such as Yixing and Zhuhai, with populations of 1.2 and 1.6 million, respectively. In close proximity to purple clay known as Zisha, Yixing has been the teapot capital of China for centuries. In Yixing, Peter Exton designed a beautifully crafted, 1,200-seat grand theatre and a 650-seat concert hall. In Zhuhai, we designed the spectacular opera house with its 90m-high, shell-shaped exterior. This is the first building that greets you as you drive over the new 55km Hong Kong–Zhuhai bridge.”

Still making an impression today as it did when it first opened in 2008, the performing arts centre within the Guangzhou Opera House remains one of the firm’s pinnacle works. “Be prepared to play a long game if entering the Chinese marketplace,” advises Fearnside. “Looking back on how our business evolved, I would say that any new company venturing into China for the first time should be prepared to invest for five years without significant return. When we received a faxed notification that we had won the Guangzhou project in 2005, it was a watershed moment for us in China. On this project, we worked with the late architect Zaha Hadid to develop the world’s first asymmetrical opera house, which has regularly been featured in the top 10 best opera houses in the world. The 10th anniversary was celebrated by a fully imported production of Franco Zeffirelli’s Aida with a cast of over 170 performers, and imported principals accompanied by the Xian Symphony Orchestra conducted by Australian, Dane Lam.”

Renowned throughout the world for its terracotta warriors and Tang Dynasty architecture, Xi’an remains Fearnside’s favourite city. “Following the completion of the 1,250-seat Xi’an Concert Hall in 2009, we embarked on the design of the opera house, which opened in 2017 with a fully imported Italian production of Turandot. The Xi’an Concert Hall and Opera Theatre both have traditional, Tang-style exteriors and modern interiors. Adjacent to them is a museum dedicated to shadow puppets, which dates back to the Han Dynasty. We have since been appointed on a new concert hall and opera theatre in Xi’an.”

Recently in Chengdu, Fearnside and Exton were commissioning a new performing arts centre attached to the Conservatory of Music. Walking back from lunch, they were passing several music shops when they came across one specialising in the care of stringed instruments. The shop was run by Lin, a graduate of the Violin Making School of America in Salt Lake City who was working in the shop established by his father, also a violin maker and repairer. Exton, who was an accomplished professional violinist before taking up acoustics, was delighted at this chance meeting. “We were welcomed with tea, and a personal tour of the workshop, complete with a demonstration of the hand tools used by Lin in a way that has not changed since the craft was established in northern Italy in the 17th century,” recalls Exton. “The violin was excellent and, on a later visit, the acquaintance was renewed as Peter used the instrument to demonstrate the fine acoustics of the violin and the new concert hall to a delighted client.”

Marshall Day Acoustics followed up its establishment of an office in Shanghai in 2008 by setting up another in Hong Kong five years later. “Local support and logistics are vital as construction normally outpaces design, meaning you have to work at a breathtaking pace,” explains Fearnside. “Our largest project to date is the Jiangsu Grand Theatre project in Nanjing, which includes a 2,300-seat opera house, a 1,500-seat concert hall and a 1,000-seat drama theatre. The project opened this year and will probably be the last of the very large, multi-venue performing arts complexes to be built in China for some time. It was extremely challenging.”

Having stepped down as CEO in 2017, Fearnside remains a principal of Marshall Day Acoustics in Australia and is committed to working with the firm, particularly in China. Despite the long train journeys, delayed flights and missed connections, together with the odd bout of food poisoning along the way, his passion for China remains all-consuming. “Establishing the business there over the past two decades and working with Peter Exton and Sir Harold Marshall has been the most rewarding time of my business life. I would often travel there overnight on a Sunday and go to three cities in five days before travelling home on Friday. Sometimes, I would spend two weeks out there, but I had to limit the amount of time travelling, so that I could spend my weekends at home to see my young son grow up.”

Over the same timescale, Chinese arts and the attendant performance venues that have sprung up to accommodate them have also matured at an accelerated rate to become the envy of the world, thanks in no small part to Marshall Day Acoustics.